Henry Moore’s Photographic Identity

Marin R. Sullivan

Moore was one of the first modern artists to exploit photography as an extended field of communication, taking and sanctioning images that emphasised the tactile interplay between him and his sculptures. Photographs of Moore at work provided iconic images that shaped public perceptions and allowed him, this essay argues, to hide behind an unchanging public persona.

In 1960 the late Anthony Caro remarked in an interview, ‘When you try to think clearly about Henry Moore you are deafened by the applause. The picture is not man-size, but screen-size. It is as if the build-up into a great public figure has got out of hand, and like a film’s big front has clouded our view of the real Moore.’1 Caro’s choice of analogy aptly speaks to Moore’s status as one of the most photographed, filmed, and exposed artists of the twentieth century. Over the course of Moore’s lifetime, the role and sheer amount of publicity dramatically increased, a shift that many, like Caro, saw as potentially detrimental to the integrity of fine artists and their work. Photographs of Moore also multiplied as his career progressed, especially during the last two decades of his life. Caro’s evocation of the ‘real Moore,’ however, suggests a fissure or paradox embedded with these images, namely, that the more the public saw Moore, the farther they got from a true portrait. Moore’s heightened visual presence within the public sphere was neither accidental nor just a result of changes in celebrity culture. Moore deployed photography in a conscious and considered manner throughout his career, using it to construct a multifaceted identity that was both true and false, that both implicated himself within his work and created a barrier between him and the public.

While few claim Moore’s embrace of photography was evidence of a fame-hungry artist, even fewer have acknowledged its prescience and complexity. Like Caro, many dismissed the inundating mass of publicity images on account of their intended function or expressed suspicion of Moore’s apparent participation in the crafting and controlling of his public image. Such cynicism is not limited to analyses of Moore, but extends to all aspects of what the art critic Lawrence Alloway referred to as the larger ‘communications network’ in which contemporary art circulated. Alloway wrote:

The network is the route for the dissemination and interaction of information, so that art appears, not only in its prestigeful links with the sacred and the visionary, but in problematic and glamorous, arbitrary and unexpected contexts as well. Publicity is not violation and reproduction is not burning in effigy. On the contrary, the work of art is sited in a continuum of human communications. There is nothing destructive in art’s proximity to other human actions and operations. On the contrary, it is part of the speculation and meditation, study and revision, to which art is subjected. Only by such a process of continuous estimation can art be experienced richly, both as it is encumbered with values and as it is provocative of uncertainty.2

Alloway was, and remains, one of the few commentators to consider publicity as more than just a necessary aspect of being a commercially successful artist. Many are quick to dismiss the photographs of Moore, to ‘burn them in effigy’ as promotional documents on the grounds that they are either innocuous or highly manipulative. They see in them complicity, whether conscious or unconscious, of an artist all too willing to be staged and manoeuvred, like a sculptor-marionette, used to project an image of the modern post-war British artist to a domestic and international public. This essay is not a comprehensive survey of either photographs of Moore or his work but uses a selection of images produced between 1930 and the early 1960s to examine how the artist shaped his public persona. Although many of the more iconic photographs of Moore date from the last two decades of his life, it was during the roughly thirty years addressed in this essay that a photographic identity became fully formed, codified through a strikingly uniform body of photographs depicting the sculptor and his work. These images are more than celebrity portraits or documents of an artist at work, and considering Moore’s involvement in their creation, attest to a far more pervasive and multifarious utilisation of photography within his greater sculptural practice.

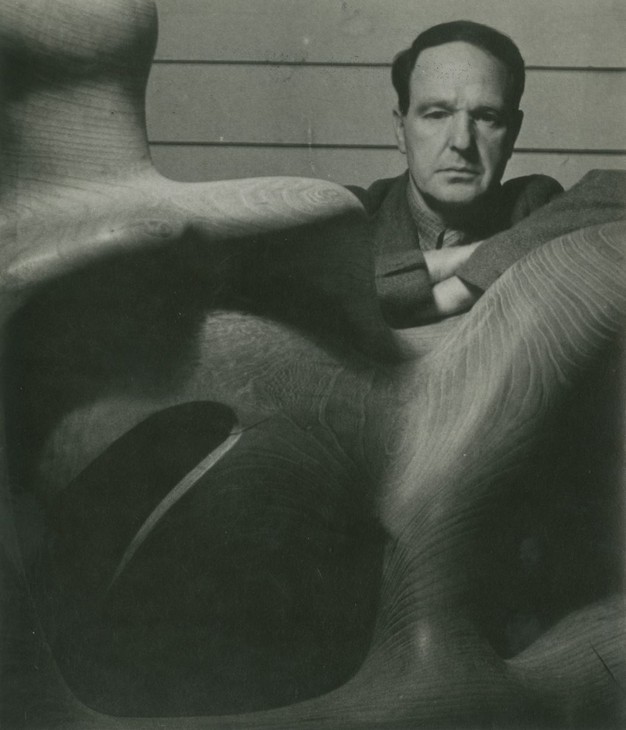

Whether shooting the images himself or working with a professional photographer, Moore used photography for a wide range of purposes: to speculate and meditate, to study and revise, and to extend the reach of his work within what Alloway called the ‘continuum of human communications’. The manner and consistency in which Moore included his own body, his own physical presence, however, is what distinguished these images. Moore positioned himself in a manner to highlight the connection to his work, to be more than simply present. In these photographs, he is seen through his sculptures, in postures that mirror their curves and angles; parts of his body enmeshed within their holes, seams, and crevices, often fused to their material bodies. The photographs enabled an inextricable, permanent physical link between Moore and his work, a visual bond that simultaneously defined Moore’s public identity and substantiated the more innovative aspects of his sculptural practice. Moore used photography to promote and document, but more specifically to transform and disperse profoundly tactile and material objects beyond their corporeal boundaries.

Photographs of and by Moore

Studies of Moore and his work have tended to bifurcate his career into pre- and post-war periods, with the former heralded for its avant-garde innovation and the latter often critiqued in light of Moore’s establishment as the pre-eminent and prototypical modern British sculptor.

But from the very beginning, and regardless of the scale of his projects or the mode of their creation, photography was a ubiquitous facet of his artistic practice.

But from the very beginning, and regardless of the scale of his projects or the mode of their creation, photography was a ubiquitous facet of his artistic practice.

Thousands of photographs produced by and of Moore over his career are now held in the Image Archive of the Henry Moore Foundation. They are housed on the same property in the Hertfordshire hamlet of Perry Green where Moore worked and lived from 1940 to his death in 1986. Many photographs are the result of Moore’s exhaustive documentation of his sculpture. These images focus exclusively on the work, often set against the backdrop of a pastoral landscape, in the manner Moore came to prefer. Other photographs of this nature also show Moore’s sculptures in his studio or the more neutral, white spaces of galleries. There are thousands more of the sculptor without his work, in purely social and familial situations: having tea with his wife and daughter, bicycling, picnicking with friends, frolicking in the sea, and holidaying in Italy. There are also numerous shots of the pomp and circumstance that came to dominate Moore’s later life and career: the public installations and unveilings, the ceremonies, and VIP tours. While these photographs provide valuable insight into who Henry Moore was as a person and how he wanted his work to be seen, this essay focuses instead on the images depicting both Moore and his work, found within the group of photographs classified by the Foundation as ‘biographical.’

Many of these photographs logically fit into such a categorical designation. They can be read as straightforward publicity images showing Moore’s life, a kind of hybrid action-shot-cum-portrait depicting Moore in the process of creating a work or proudly presenting the finished product. From the very beginning of his career Moore appeared comfortable staging photographs of himself with his work, even if these types of pictures exponentially increased when he and his wife Irina settled in Perry Green. As art historian Pauline Rose and others have noted, photographs of Moore, like the text-based press coverage often accompanying them, tended to highlight aspects of his personality, his domestic situation, his ‘Englishness’ and his ‘simple way of life’, portraying him as ‘a modest, home-loving family man who did not seek the limelight’.3 The photographs, over and over again, project an idyllic country life and depict Moore as dedicated to the sole pursuit of creating and advancing modern British sculpture, so convincingly that, to this day, they continue to saturate and dominate the public consciousness as a congealed, impermeable vision of Moore as a conservative, establishment figure – a reserved, if highly popular, and financially successful artist living his life in quiet contentment. Moore was not Warholian in his approach to publicity or even concerned with being famous, but neither was he as droll and simplistic as such a vision might suggest. The sheer abundance of photographs showing Moore, not simply as a personality but with and within his work, suggests an artist highly attuned to and aware of both the necessities and possibilities of promotion and public exposure.

Moore was an avid amateur photographer. Cameras, film, other photographic equipment, and copious photographic prints and scraps filled his home office and studios at Perry Green, which remain as they were during Moore’s life under the maintenance of the Henry Moore Foundation. There are also numerous photographs showing the sculptor in the process of photographing his work, like the 1953 image by Chris Ware (fig.1) that captures Moore in front of a sculpture, angled slightly upward, while he fixes the work into the perfect position on a small plinth in front of a neutral backdrop, bathed in the natural light streaming through his studio’s clerestory windows. As this images attests other photographers were behind the camera for the majority of photographs that came to define his public identity. Moore frequently welcomed reporters and photojournalists to Perry Green, and as his fame increased, attracted the interest of many other independent photographers eager to shoot him, his work and his lifestyle.

Larry Burrows

Henry Moore at work in his Maquette Studio 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Larry Burrows, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Larry Burrows

Henry Moore at work in his Maquette Studio 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Larry Burrows, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Sculptor Henry Moore sits in an aged wicker chair on a crumpled cushion. He is small and compact (5 ft. 7 in., 154 lbs.), with a high-domed face that is benign yet cragged. Thinning strands of greying hair stretch errantly across his head. From beneath brows that jut at least an inch beyond pale blue eyes, he stares intensely at a small plaster shape held in his left hand. The right hand, thick wristed and broad, with straight fingers that are surgically muscular, holds a small scalpel. In a few minutes, the chunk of thumb-shaped plaster takes on form.4

Photographs and articles emphasising similar characteristics of Moore and his work appeared frequently, in a wide variety of media outlets throughout the decades before and after the war. These included regional, national and international newspapers, more specialised arts publications like Art News and Studio International, and populist photo-oriented magazines that flourished in the post-war period like Picture Post and Life. Photo-spreads also appeared in perhaps less expected sources, including society publications like the Tatler, fashion magazines like Vogue and even the long-running Italian celebrity gossip glossy Gente.5 On 9 November 1960 the Tatler, included a feature article called ‘Henry Moore at Home’, which presented the sculptor as avant-garde artist, similar to the approach taken by Time a year prior. The Tatler article, however, also took the opportunity to criticise the British public for being too provincial or uneducated to grasp the importance of Moore’s work. The article declares, ‘But by the majority, whose experience of it [Moore’s work] will be limited to one or two sensationalised photographs in the popular newspapers, it will be dismissed with a brief smile or sneer as the latest joke by the man who puts holes where stomachs ought to be.’6

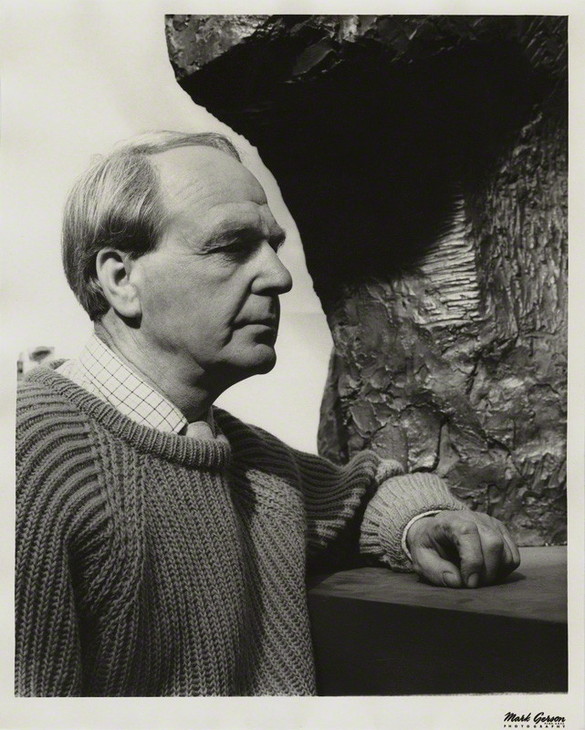

This comment conveys something of the power of photographs in shaping public perceptions of Moore’s work and suggests that in order to truly appreciate his sculpture it was necessary to also see a range of pictures of the artist at home and at work. The magazine included photographs of the interiors of Moore’s home, fitting for a publication like the Tatler perhaps but by no means limited to it in these years. Indeed, the admonishment of ‘sensationalised photographs’ is curious, as the photographs in the Tatler were remarkably similar to the photographs that appeared in every publication, high or lowbrow. They showed the artist in his studio, almost completely obscured behind a larger plaster model of a reclining figure, and a full-page photograph at the beginning of the article (fig.3) of Moore in three-quarters profile, the contours of his face and the texture of his sweater mirroring the forms of his sculpture, and they could have as easily have been images from the Manchester Guardian or Picture Post.

The uniformity of Moore’s photographic identity, even across such a long period of time and across a wide range of outlets, is due in part to the control exerted by the artist, and his ability to cultivate a select group of photographers, especially during the last two decades of his life. David Finn, John Hedgecoe, Errol Jackson, and Gemma Levine shot the most well known, iconic, images of Henry Moore. They produced beautiful photographs of Moore and his work, over several years, in large quantities, often for extensive, independent projects. Hedgecoe’s Henry Spencer Moore (1968) was one of the first photo-essays on Moore to be published as a book.7 A collaboration with Moore, who also contributed the text, the volume included images of Moore at work and at home, as well as photographs of the landscape and coal mines of the artist’s native Yorkshire. As critic Robert Hughes remarked in his review of the book for the Spectator, the ‘aims of this luscious treatment is to give the reader the illusion that he “knows Moore”’.8 While Hughes’s account of the book expresses a fatigue similar to Caro’s over the public imaging of Moore, it acknowledged that the volume offered an opportunity to grasp better Moore’s own artistic preoccupations. Hughes’s major criticism was the format itself:

My point rather is that photo-essays of this kind (even when they are as finely shot as Hedgecoe’s) have little use except in a society which responds to the work of its artists largely in terms of glamour, personality, and mark. Far from bringing the audience closer to the object, they offer the illusion that profound alienation between artist and audience, which can only be closed by the work, can somehow be papered over by other means.9

Whether or not Hughes was happy about it, Henry Spencer Moore exemplified a shift in the status of artist in the public sphere and how their images circulated within it. Photographers like Hedgecoe or Jackson, who worked as a personal photographer for Moore between 1961 and 1986, generating over 25,000 images, excelled at creating memorable photographs of the sculptor and his work. Without devaluing their artistic achievements or authorial autonomy, the images they produced reveal, however, that by the early 1960s Moore’s public image and the ways in which that image was communicated photographically had already been firmly and persistently established. Their images bear striking resemblance to those taken in the 1950s, the 1940s, and even the 1930s; again not because of any lack of artistic originality on their part, but because it was always Moore who was behind the photograph – even if he appeared within it. Jackson, for example, recalled Moore’s apparent pleasure in relinquishing the actual process of photographing to someone else, telling the photographer, ‘I take my own photographs, but always say a private prayer when I press the shutter, and would be grateful to work with a photographer who can come to an understanding of what I want from my photographs in relation to my work.’10

Moore’s collaborations with photographers in the last two decades of his life indicate a continued, and possibly increased, importance of photography within his artistic practice. The resulting images, however, also suggest that anyone wanting to photograph Moore needed to conform to the vision he wanted to promulgate. By the 1960s, it was more a question of maintaining rather than constructing his image, as the conventions and visual attributes of his public photographic identity were fully established.

Material bodies

The declaration that photographs played a crucial role in the formation of a public persona could be made of almost any cultural figure of the twentieth century. The images of Moore and his work created between 1930 and 1960, however, were not simply a means to promote the sculptor as a personality or to increase his name recognition. They also testify to the creation of a remarkably consistent and controlled photographic identity and what it could communicate about his greater sculptural practice. I argue that no matter who took the photograph, when or where it was shot, or where it would eventually be seen, the overall aesthetic and formal framing of these images remain strikingly similar. Through photography, Moore seized the opportunity to substantiate, in a very public manner, what he saw as most important about his work; to visually corroborate the claims of materiality and tactility made by him and his most ardent supporters, for example, the critic Herbert Read, in regards to his sculpture.11

Henry Moore at work in his studio 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Felix Man, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore at work in his studio 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Felix Man, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

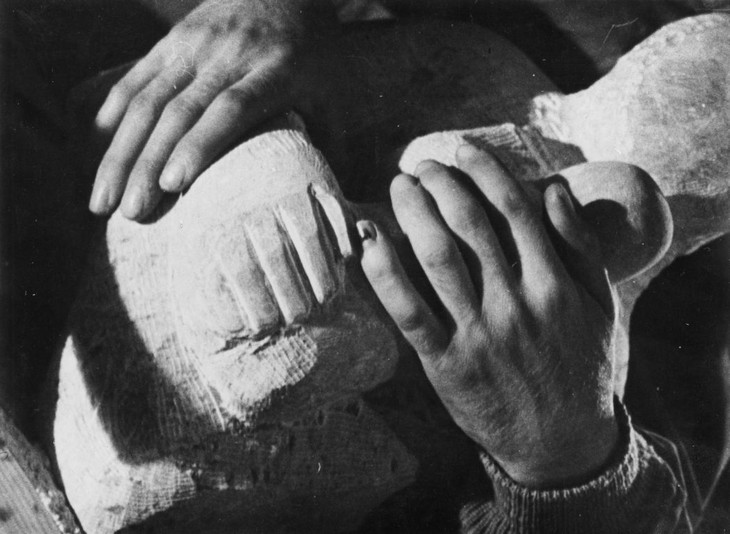

Anne Wagner has recently and persuasively suggested that the photographs of Moore’s hands possess a ‘distinctly structured message’ that ‘delimit, perhaps even define, our view of the man’.15 They became a powerful visual declaration of tactility, which for Moore was the defining condition of sculpture, even if his tactile engagement with materials changed as his career progressed. For Wagner, such images reveal how as Moore’s work grew in size and utilised less direct processes, the sculptor continued to emphasise ‘the formal and theoretical implications of the figure of the hand,’ through photography and drawing.16 The increase in photographic images coincided with a decline of Moore’s physical engagement with his finished works, but tactility was always present in his sculptural practice.

Thea Strove

Photograph showing Henry Moore holding a half-carved figure 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Thea Strove, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Thea Strove

Photograph showing Henry Moore holding a half-carved figure 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Thea Strove, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

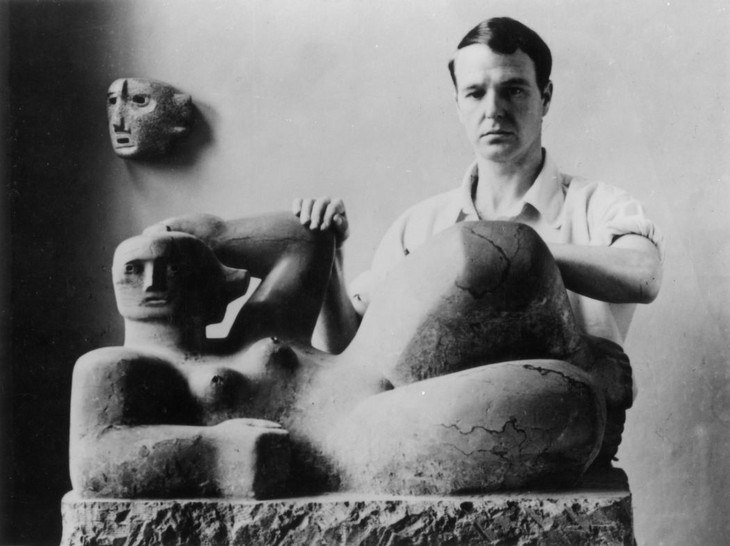

The physical encounter between Moore and his work expressed in these photographs was not limited to his hands. For all the abundance of images showing Moore’s hands, there are just as many in which they are hidden in pockets or behind a sculpture, or de-emphasised altogether as simply one element of Moore’s body. Even in the frontispiece image of Read’s Henry Moore, Sculptor, Moore’s hand establishes a marked point on contact, but the power of the image, or rather the interchange captured in the image, comes from the entirety of his corporeal presence: from the alignment of his head with the that of the ‘mother,’ the manner in which his right arm positioned at angle to mirror that of the ‘mother’s’ left arm, and the effacement of his torso behind the sculptural object. This type of mirroring and enmeshment of material bodies occurs across so many photographs of Moore and his work it is hard to imagine it not being a consciously deployed strategy.

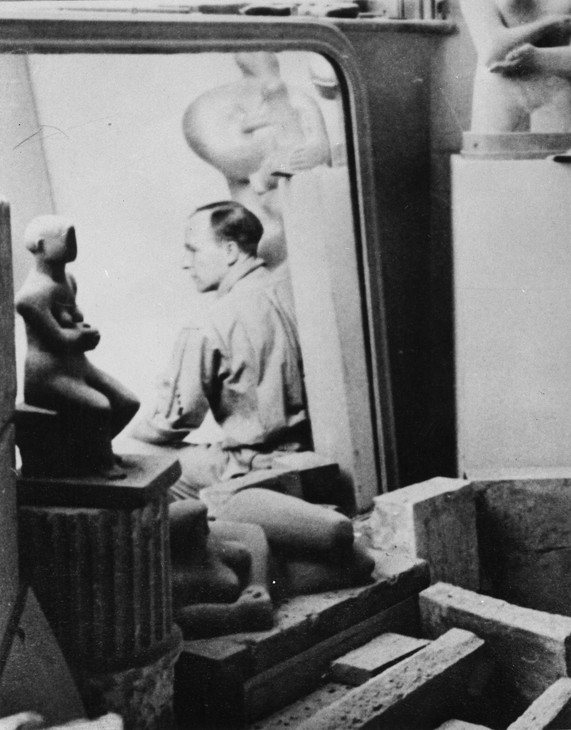

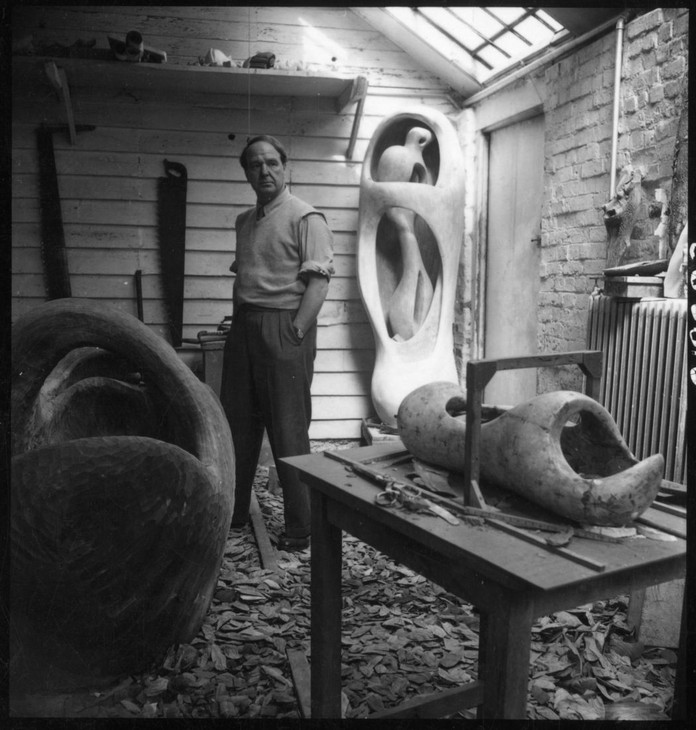

In a photograph by Bill Brandt of c.1948 (fig.6) Moore stands in his Top Studio in Perry Green, behind one of his large, wood reclining figures. Moore’s upper body appears to emerge from the body of the sculpture, his folded arms, shoulders, and head visible through a dip in the contour of the work. Even when not shown immersed within one of his sculpture’s characteristic holes or touching a work, his body echoes the forms of his sculptures, his posture mimicking the verticality of his more monolithic works or the sinuous lines of his more abstract, organic work. In a photograph of 1952–3 taken by Roger Wood (fig.7), Moore stands toward the back of the Top Studio on a floor strewn with the remnants of his work. He looks off to the side, his hands tucked into his pockets, surrounded by the tools and raw materials of his trade. His right leg appears to merge into an incomplete sculpture sitting on the ground. This work, along with the two other pieces visible in the frame, triangulate around Moore, making him the focus of the image while connecting his body to their own physical presences. His posture and the folds in his clothing mirror the curving lines of the plaster version of Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3, visible over his left shoulder.

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure c.1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Bill Brandt, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure c.1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Bill Brandt, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure and Mask c.1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure and Mask c.1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

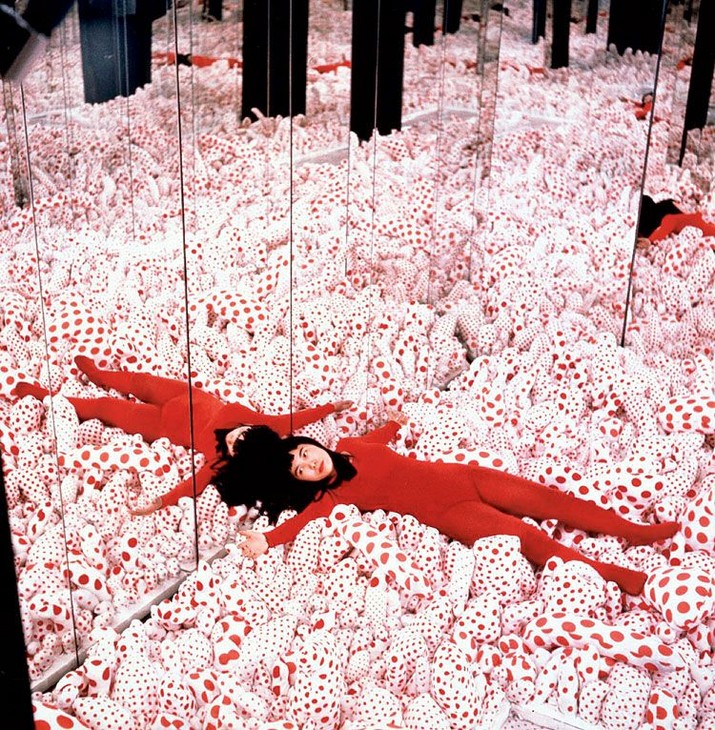

Moore’s assiduous attention to the posture of his own body and its contact, whether visual or physical, with his work appeared in photographs from the 1930s. After the war, however, other artists followed suit. Moore may not often be compared to vanguard artists of the 1950s and 1960s like Allan Kaprow, Yayoi Kusama or Pino Pascali but he shared with them a complex and extensive utilisation of photography to support the concept of their practice. Like Moore, this younger generation of artists constructed their own public personas through photography, implicating their own bodies within the constitution of their work through the photographic image. The 1952 Wood photograph of Moore and a widely reproduced photograph of Kaprow standing atop the hundreds of the disused tires comprising his work Yard (fig.9) at the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1961, function in strikingly similar ways. Neither image focuses exclusively on the artist himself as in a conventional portrait, nor does either show enough of the work(s) in question to serve as a straightforward historical document: instead, in each a profound connection between artist, material, and space becomes apparent.

In part, these kinds of images perpetuated the long-established tradition of photographing the artist at work. They can be related to the now iconic shots – by Ugo Mulas of Lucio Fontana slicing a canvas, for example, or Hans Namuth’s images of Jackson Pollock – that highlight the connection between the body of the artist and the resultant work of art. The photographs of Moore, however, were not limited to ‘action shots’ of the artist carving a block of wood or moulding plaster onto a wire frame. The photographs created by Kaprow and the younger generation of artists likewise, rarely showed the artist in the actual process of creating a work (a result perhaps of a greater shift in their practices that saw them move away from hand carved or modelled modes of sculpting altogether). What comparing the photographs of Moore and his work to those by Kusama or Pascali reveals is how they all utilised photography within their artistic practices in a radically new manner; not simply as a means of self-portraiture or record-keeping but as a means of operating in and exploiting the multifaceted space between object, image, and persona.

Claudio Abate

Pino Pascali posing with Vedova Blu (Blue Widow) 1968

© Claudio Abate

Fig.10

Claudio Abate

Pino Pascali posing with Vedova Blu (Blue Widow) 1968

© Claudio Abate

The images of Moore where he is posing with his work and ‘seems to have become a sculpture himself’ are the most powerful examples of how he straddled the liminal space between what was and how it was depicted, between what was real and tactile and what could be projected outward as an image. Moore’s corporeal performance enacted for the camera was perhaps not as dramatic as Pascali’s, seen in a photograph by Claudio Abate from 1968 (fig.10), playfully contorting his body under his Vedova Blu (Blue Widow). Moore’s consistent and considered attention to the details of how he would be depicted, however, was just as deliberate and effective in establishing the message he wanted to achieve through photography.

Yayoi Kusama

Infinity Mirror Room. Phalli's Field Installation view from Floor Show exhibit at the Castellane Gallery, New York, 1965

© Yayoi Kusama

Fig.11

Yayoi Kusama

Infinity Mirror Room. Phalli's Field Installation view from Floor Show exhibit at the Castellane Gallery, New York, 1965

© Yayoi Kusama

The photographs of Kusama, like so many of those created by Moore over the prior three decades, wove together the presence, the public persona of the artist, while at the same time using those images to efface themselves altogether. Like Kusama, Moore crafted a repetitive if distinctive self-image for public consumption, and used that very image to disappear within his work. In photograph after photograph Moore appears clean-shaven, with neatly groomed hair, clad in pressed trousers, Oxford shoes splattered with plaster, and a button-down shirt, sleeves rolled, often with a tie tucked behind a (sleeveless) jumper or apron, depending on the season. In fact, save for his hair greying and a few more wrinkles, Moore’s appearance rarely changed, even with the passage of decades. A general disinterest in fashion could account for such phenomenon, but it is also suggestive of a decision to establish an easily recognised identity, one which would contribute a layer of additional meaning to an image without distracting attention away from his work. Moore’s apparel, like his hands, body, and overall emphasis on tactility, projected a consistent image but also one that was relatable and easily consumable for a large swathe of the general public, especially those of the working class. His appearance was not that of the eccentric artist or an elite country gentleman, but a rather ordinary, everyman. The regularity of his modest clothing choices and grooming habits speaks to an overall concern with visibility and invisibility, a deliberate directing of the viewers’ attention to specific aspects of an image while enabling others to blend into the overall picture.

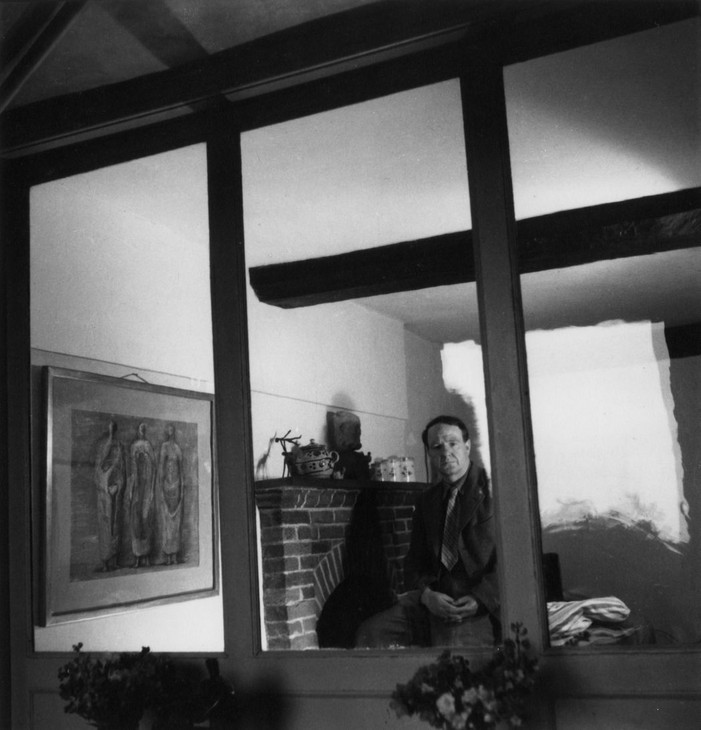

Photography allowed Moore to expand outward and reflect inward, as his work and public image became indistinguishable over the course of his career. Lost in this fusion of artist, public, and work, to return to Caro, was ultimately the true image of Henry Moore. For as much as Moore inserted himself into photographs and thus into the public sphere, in image after image he visually asserts a certain distance. In many images his sculpture used as a kind of visual barricade. In others, like one taken in the Top Studio in 1945 (fig.12), Moore’s presence is pronounced and yet he is detached, standing in the background, separated from the viewer by two of his large reclining figures. He is positioned in such a way that his body visually fuses with his sculpture. The left side of his body mimics the verticality of the pedestal, his left arm connecting to the edge of the sculpture atop it. The resting arm of one of the large figures effaces the right side of his body. In one of the more unusual images found in the biographical archive, taken by F.J. Goodman a year later (fig.13), Moore is depicted not with one of his sculptures but alongside one his drawings, framed and hung on one of the walls of his home. Like the drawing of his sculpture, Moore himself is framed behind glass, the image shot through a window from the outside. The viewer is granted access to him as only at a distance.

Henry Moore in his Top Studio 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore in his Top Studio 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore at Home 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: F. J. Goodman, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore at Home 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: F. J. Goodman, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Permeable boundaries

Artists of a later generation like Kusama or Pascali pushed the boundaries of sculpture, embracing new materials, new display tactics, and ever-more extraneous, ephemeral and performative elements, which in turn integrated and relied on subsequent photographic and filmic documentation. Moore, no matter where he displayed his work or how he photographed it, always remained committed to a definition of sculpture as a transformation of raw material into a three-dimensional art object. But it would be a mistake to only see his work as autonomous, contained objects. In one of the rare occasions he mentioned photography, Moore stated:

Some sculptures do, of course, only have one point of view; like so many well-known works that are always photographed from the one position. But I am concerned with sculpture which presents an ever-expanding and deepening experience as you move around, so that its totality can only be apprehended in the act of continuity of movement.21

The core of Moore’s work may have been its materiality, but the photographs he took of his pieces and his eagerness to include himself, his own body, within these images suggest a far more expansive conception about the constitution of sculpture. Photographs enabled Moore to promote his work, and they also helped expand the network in which they circulated and communicated. Through these photographs Moore created dialogues between multiple sculptures, installations, and environments. With photography Moore repeated and reiterated key formal attributes of his work, and further emphasised its tactility and materiality. Perhaps, most radically, he used photographs as the connective tissue among these various elements. As the cultural theorist Rudolf Arnheim suggested in 1948, Moore’s work evokes a ‘two-way relationship,’ a ‘dramatic interchange of forces’ between the physical properties of the object and its surrounding space. Arnheim wrote:

The sculptural body ceases to be a self-contained, neatly circumscribed universe. Its boundary has become permeable. It has been inserted into a larger context ... In other words, the tendency to avoid isolation and delimitation, to unite parts in an exchange of forces rules not only within the figure but is applied also to the relation of figure and environment. This is a daring extension of the sculptural universe, made possible perhaps by an era in which flying has taught us through vivid kinaesthetic experience that air is a material substance like earth or wood or stone, a medium which no only carries heavy bodies but pushes them hard and can be bumped into like a rock.22

Arnheim was referring to the manner in which Moore’s sculpture, already in 1948, engaged with the space it occupied, extending outward and taking into account ever more involved environments. He was probably not thinking of photography as an extension of the sculptural universe, and yet this is exactly what Moore achieved in constructing his photographic identity, visible in one of his earliest and most striking photographs (fig.14). Taken in 1930, the image shows the interior of Moore’s Hammersmith studio, flooded with natural light streaming in from the window at the topmost edge of the frame. Below the windowsill, covered with small, roughhewn pebbles and stones, three carved sculptures rest on a column fragment, pedestal, and pile of cut stone blocks, respectively. Leaning on the wall behind them is a framed mirror, a reflection of a fourth, a larger sculpture, Moore’s Mother and Child, captured on its surface. At the centre of this web of sculptures sits Moore, almost an afterthought in the picture and yet provocatively captured in the centre as a reflection, his back and upper torso discernible in the mirror and his face turned in profile. His body, clad in a light button-down shirt and trousers, both exists within this space and projects outward. He is visible and invisible, close but distant. This is an image of the artist looking at his work and instructing others how to do the same. It implicates his own presence with those of his sculptures, and suggests ‘a dramatic interchange’ of the ‘forces’ operating in the space they are shown. The inclusion of the mirror and the hint of window also suggest the universe beyond. Seen in this way, Moore was one of the first artists to understand that photography offered a larger context in which sculpture could operate, one that, to return to Alloway, may be ‘problematic,’ ‘glamorous,’ and ‘unexpected,’ but one that allowed it to circulate beyond its physical boundaries and live ‘in a continuum of human communication.’

Notes

Lawrence Alloway, ‘Art and the Communications Network’ 1966, reprinted in Richard Kalina (ed.), Imagining the Present: Context, Content, and the Role of the Critic, London 2006, p.119.

Pauline Rose, ‘Henry Moore in America’, Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975, Los Angeles 2001, p.33. See also Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, and Dorothy Kosinski, ‘Some Reasons for a Reputation’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001.

Alan Roberts, ‘Henry Moore at Home’, Tatler, 9 November 1960, pp.34–9. Raymond Mortimer, ‘Henry Moore’, Vogue, 15 January 1947, pp.80–1, 146. ‘Lo Scultore si Fotografa’, Gente, 11 September 1968, pp.74–5. For a full list, see the Henry Moore Bibliography, Hertfordshire 1992.

Henry Moore as quoted in Estelle Lovatt, ‘Henry Moore at Work’, Errol Jackson: Photographer, 1914–1996, Ellingham 1998, p.7.

See David J. Getsy, ‘Tactility or Opticality, Henry Moore or David Smith: Herbert Read and Clement Greenberg on the Art of Sculpture’, 1956, in Michael Paraskos (ed.), Rereading Read: New Views on Herbert Read, London 2007, p.152–65.

Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, ‘Introduction’ in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, p.7.

For other examples of the relationship between photography and sculpture, including analyses of Constantin Brancusi, David Smith, and Carl Andre, see Geraldine Johnson (ed.), Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension, Cambridge 1998.

See, for example, Penelope Curtis and Fiona Russell, ‘Henry Moore and the Post-War British Landscape: Monuments Ancient and Modern’, and Robert Burstow, ‘Henry Moore’s “Open-Air” Sculpture: A Modern, Reforming Aesthetic of Sunlight and Air’ in Beckett and Russell 2003.

Anne Wagner, ‘Moore’s Later Sculpture: The Space Between Knuckles’, Henry Moore, Late Large Forms, exhibition catalogue, Gagosian Gallery, London 2012, p.170.

Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934.

Jon Wood, Close Encounters: The Sculptor’s Studio in the Age of the Camera, exhibition catalogue, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds 2001, [p.15].

Marin R. Sullivan is an Assistant Professor of Art History in the Art Department of Keene State College, New Hampshire

How to cite

Marin R. Sullivan, ‘Henry Moore’s Photographic Identity’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www